NLI Research - The True Potential of the Japanese Economy

The NLI Research Institute has published an article titled "The potential growth rate can be changed: The true potential of the Japanese economy," authored by Taro Saito. The following is intended to reflect the essence of this work in English translation

1. The Stagnation Paradox: Challenging the Narrative of Inevitable Decline

Japan's post-pandemic economic recovery is a story of profound underperformance, a divergence from its global peers so stark it demands a fundamental re-evaluation of the nation's perceived economic limits. Correctly diagnosing the root cause of this sluggish growth is of paramount strategic importance; a misdiagnosis leads to ineffective, and potentially counterproductive, policy solutions.

The divergence in performance is stark. A comparison of real GDP, benchmarked against 2019 pre-pandemic averages, reveals that Japan's economy has expanded by a mere 2.1%. In contrast, the United States has surged ahead by 14.7%, and the Eurozone has grown by 6.1%. On an annualized basis over the past five years, Japan’s growth rate of 0.4% is dwarfed by the U.S. rate of 2.5% and the Eurozone's 1.1%.

The conventional explanation for this persistent underperformance points to a structural ceiling: a very low potential growth rate. Official estimates, such as the OECD’s 2025 forecast of just 0.17% for Japan, appear to validate this narrative of inevitable decline. This view suggests that Japan is fundamentally constrained by its supply-side capacity and that ambitious growth targets are unrealistic.

This analysis posits a more dynamic and optimistic diagnosis: Japan's potential growth rate is not a fixed, structural barrier but a dynamic estimate that is heavily influenced by the trajectory of actual, demand-driven GDP. This paper argues that Japan's economic fate is not predetermined by demographic and supply-side constraints alone. Decades of anemic demand have created a self-fulfilling prophecy, artificially suppressing the nation’s measured potential. To chart a new course, one must first deconstruct the very concept of the potential growth rate itself.

2. Deconstructing the Potential Growth Rate: An Estimate, Not a Destiny

To challenge the conventional narrative of supply-side limitations, it is essential to understand what the potential growth rate (PGR) truly represents. Far from being a hard physical limit on the economy's productive capacity, the PGR is a statistical estimate—an unobservable variable calculated through various economic models. Its nature as an estimate, subject to revision and methodological interpretation, is the critical insight needed to rethink Japan's economic strategy.

Different official bodies produce different estimates for this unobservable variable. Historically, the figures published by the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and the Cabinet Office have shown significant divergence. For example, during the 2009-2010 period following the global financial crisis, the BoJ’s estimate fell into negative territory while the Cabinet Office’s remained positive. Conversely, in 2013-2014, the BoJ’s estimate recovered to over 1% while the Cabinet Office’s remained stubbornly in the low 0% range. These discrepancies underscore the fact that PGR is not a single, universally agreed-upon number.

More importantly, these estimates are subject to substantial retrospective revisions. An analysis of the BoJ's data reveals that the PGR calculated for a specific period can be revised significantly—both upwards and downwards—years after the fact. The estimate for the mid-2010s, for instance, has been adjusted multiple times as new economic performance data became available. This demonstrates that the assessment of past potential is heavily dependent on subsequent economic outcomes.

The core evidence underpinning this paper's argument lies in the exceptionally high statistical correlation between Japan's actual real GDP growth and the BoJ's estimated PGR. Analysis shows a correlation coefficient as high as 0.965, indicating that the two metrics move in near-perfect lockstep.

The technical reason for this high correlation is embedded in the calculation methodology itself. A key component of the PGR is Total Factor Productivity (TFP), which is not directly measured but is calculated as a residual—what is left of actual GDP growth after accounting for capital and labor inputs. This means actual GDP data is a primary input for estimating TFP. Consequently, a sustained period of low actual growth will mechanically produce a low calculated TFP, which in turn drags down the overall estimate for potential growth.

This strong, methodologically-driven link between actual and potential growth is not a weakness but an opportunity. It implies that policies capable of elevating aggregate demand and driving higher actual growth can, in turn, elevate Japan's perceived economic potential.

3. The Power of Demand: A Forward-Looking Simulation

Having established the tight statistical link between actual and potential growth, we can now demonstrate the causal power of demand. To quantify this relationship, a simulation was conducted based on the NLI Research Institute's proprietary model, projecting how different trajectories of actual GDP growth would impact the calculated potential growth rate (PGR) through the end of fiscal year 2027. The results provide compelling evidence that demand-led growth can fundamentally reshape Japan's economic capacity.

The simulation projected the PGR under three distinct scenarios for actual GDP growth, with the following outcomes:

- 2% Growth Scenario: If Japan sustains an annualized real GDP growth rate of 2%, the potential growth rate is projected to rise to 1.3% by the end of fiscal 2027.

- 1% Growth Scenario: With a sustained actual growth rate of 1%, the potential growth rate rises more modestly to 0.8%.

- 0% Growth Scenario: In a scenario of zero growth, the potential growth rate falls, eventually turning negative at -0.0%.

A critical insight from this simulation is that future growth trends retroactively change the assessment of current potential. Under the optimistic 2% growth scenario, the PGR for the first half of fiscal 2025 is revised upwards from its current estimate of 0.6% to 0.9%. Conversely, in the pessimistic 0% growth scenario, the same period's PGR is revised downwards to just 0.2%. This confirms that our understanding of today's economic potential is conditioned by our path tomorrow.

An analysis of the components driving these changes reveals that the fluctuation in the PGR is primarily driven by the calculated Total Factor Productivity (TFP) growth rate. Because TFP is calculated as a residual of actual GDP growth after accounting for capital and labor, sustained high growth in the economy is interpreted as a significant increase in productivity, thereby lifting the entire potential growth estimate.

The simulation proves that raising Japan's potential growth is an achievable policy goal. The key to unlocking this potential lies in correctly diagnosing and decisively solving the long-standing weakness in Japan's domestic demand.

4. Diagnosing Japan's Decades-Long Demand Deficit

The possibility of raising the potential growth rate through demand-side stimulus is not merely theoretical; it is a practical imperative. To formulate an effective strategy, one must first dissect the two primary components of domestic private demand—household consumption and business investment—to identify the specific points of failure that have suppressed growth for decades.

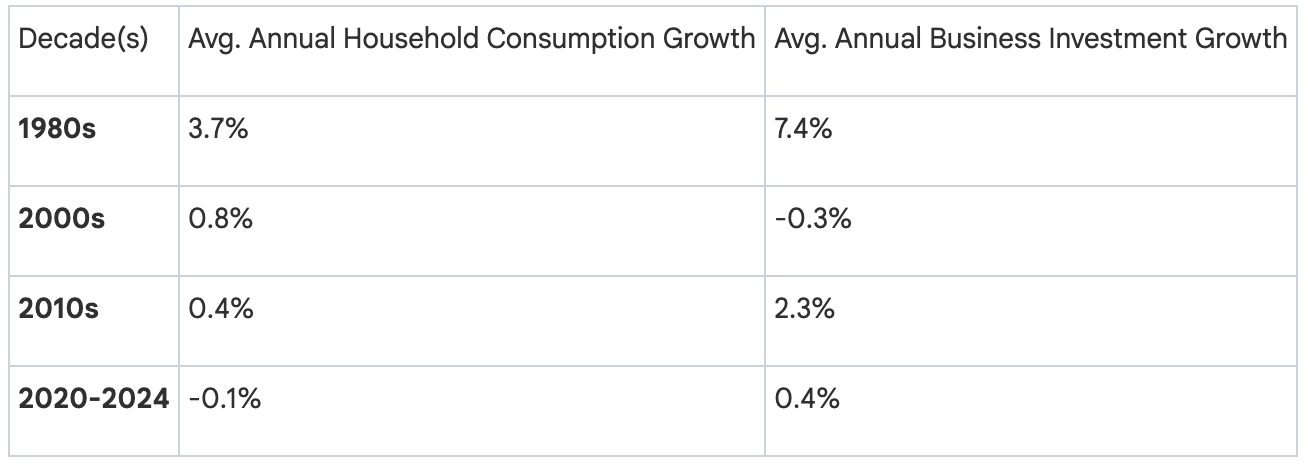

Long-term data illustrates a dramatic and sustained slowdown. The robust growth of the 1980s has given way to decades of stagnation, particularly in the core drivers of the domestic economy.

4.1 The Household Consumption Conundrum: It's Income, Not Savings

A common misconception attributes Japan's weak consumption to a culture of excessive saving or deep-seated anxiety about the future. The macroeconomic data, however, tells a different story. The household propensity to consume—the share of disposable income spent—has been on a long-term upward trend, reaching 98.5% in 2023. This indicates that households are spending nearly all of the income they receive.

The true cause of consumption stagnation is not a reluctance to spend but a chronic lack of growth in what households have available to spend: their real disposable income. This is substantiated by the steady decline in the household sector's share of national disposable income. On a gross basis, this share fell to a record low of 55.0% in 2023, a staggering decline from the nearly 70% share households commanded in the 1980s. Simply put, a shrinking slice of the national economic pie is flowing to households, leaving consumption growth starved of fuel.

4.2 The Corporate Investment Malaise: A Crisis of Expectation

The stagnation in business investment presents a parallel challenge. The primary constraint is not a lack of available funds—corporate balance sheets are healthy—but a persistently low "investment propensity," or the willingness of firms to invest their cash flow. This chronic underinvestment is not irrational; it is a direct consequence of the stagnant household demand detailed previously, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of low growth.

Prior to the 1990s, the corporate investment propensity was consistently well over 100%, meaning firms actively borrowed to invest more than their internal cash flow, signaling strong confidence in future growth. Since 2000, however, this propensity has remained significantly below 100% and hit a record low in the low 60% range in 2010. For over two decades, corporations have limited their investments to less than what their cash flow would allow.

This chronic underinvestment is directly linked to pessimistic corporate expectations about Japan's future growth prospects, which has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The dual challenges of stagnant household income and depressed corporate investment expectations must be addressed simultaneously to break the cycle of stagnation.

5. A Virtuous Cycle by Design: The Strategic Pathway to Revitalization

Revitalizing Japan's economy requires a deliberate policy intervention designed to break the decades-long cycle of stagnation and initiate a virtuous cycle of demand, investment, and growth. Having diagnosed the core problems as stagnant real household income and pessimistic corporate expectations, the strategic solution becomes clear. The most effective starting point is to directly and structurally address the erosion of household purchasing power.

A specific, unresolved policy issue lies at the heart of this problem: "bracket creep." This phenomenon occurs when inflation pushes nominal wage increases into higher marginal tax brackets. Even if a salary increase matches inflation, the household’s tax burden rises, resulting in a real tax increase and a net loss of purchasing power. This systemic flaw negates the benefits of wage growth and acts as a constant drag on consumption.

The core policy recommendation of this paper is therefore to index the national income tax brackets to the rate of inflation. This is not a one-time tax cut but a permanent structural reform designed to protect the real value of household income against inflation. By ensuring that nominal gains are not silently taxed away, this policy can trigger a powerful, self-reinforcing chain reaction.

This strategy is designed to create the following virtuous cycle:

- Boosted Real Income: Indexing tax brackets ensures that nominal wage gains translate directly into higher real disposable income for households, preserving their purchasing power.

- Increased Consumption: Higher real income directly fuels sustained growth in household consumption, the largest and most stable component of GDP.

- Improved Corporate Outlook: A clear, upward trend in domestic demand provides a powerful signal to the corporate sector, shifting growth expectations from pessimistic to optimistic.

- Revived Business Investment: With an improved outlook on future demand, a rising consumption trend compels corporations to raise their investment propensity, unlocking retained earnings to invest in new capital, technology, and expansion.

- Elevated Potential Growth: The combination of higher consumption and revitalized investment drives actual GDP growth higher. As demonstrated by our analysis, this sustained increase in actual growth leads directly to an upward revision of the nation's measured potential growth rate.

This strategic pathway is not merely about providing a short-term stimulus. It is about fundamentally reshaping expectations and creating a durable, demand-led framework for growth that breaks the psychological and statistical patterns of stagnation.

6. Conclusion: Redefining Japan's Economic Potential

For too long, the narrative surrounding the Japanese economy has been one of managing inevitable decline. This paper has argued that this conclusion is based on a misinterpretation of a key economic indicator. Japan's low potential growth rate is largely a symptom of decades of insufficient domestic demand, not an immutable structural constraint dictated by demographics or destiny.

The analysis has shown that the potential growth rate is a malleable statistical estimate that follows the trajectory of actual economic performance with a remarkably high correlation. The persistent demand deficit that has suppressed this performance is rooted in two core failures: stagnant real household income, which has choked consumption, and a resulting pessimism in the corporate sector that has stifled investment.

The solution, therefore, is not to accept these perceived limits but to actively challenge them. By implementing a structural reform to address tax bracket creep—indexing income tax brackets to inflation—policymakers can provide a permanent boost to real household disposable income. This single act can serve as the catalyst for a virtuous cycle, where rising consumption restores corporate confidence, which in turn unlocks investment, drives actual growth, and ultimately raises the nation's measured potential.

Japan's economic future is not pre-written by its past performance. It is time to stop seeing the potential growth rate as a ceiling and start treating it as a target—a target that is fully attainable once policymakers commit to unshackling domestic demand.